Deep (Energy) Takes: Decoding NEPA and Cautious Optimism About Trump's Energy Executive Orders

Decoding How NEPA Works, How NEPA Kills Our Fight to Net Zero and our Quest for Abundant Energy Capacity, Cautious Optimism for Trump's Energy Executive Orders

Hi Deep (Tech) Takes Friends! 🧑🔬👋

In our last two posts, we refined our energy intuition, unpacked energy learning curves, and explored why some technologies follow them while others don’t. That foundation will be helpful as we build on it in this and future posts.

Today’s post takes a slightly different turn. While this blog was originally intended to focus on deep tech and steer clear of U.S. policy, laws, and regulations, the scope of this energy deep dive makes that hard to avoid. Ignoring the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Trump’s recent executive orders on energy would overlook two key factors that directly impact project development and timelines in the U.S. I’ll keep it brief and focus on the essentials.

How The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Can Derail the Fight to Net Zero

In his in-depth post How NEPA Works, Brian Potter—author of the excellent blog Construction Physics—explains the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) as a law requiring all U.S. federal agencies to produce an environmental impact statement for any action likely to have significant environmental effects. More specifically, NEPA mandates a “detailed statement” outlining the environmental impacts of any “major federal action.” This can include permits or licenses for large infrastructure projects like solar or wind farms, launch approvals for private aerospace companies like SpaceX, or federal funding for highways. It also applies to major policy shifts, such as changes to the Forest Service’s land management practices.

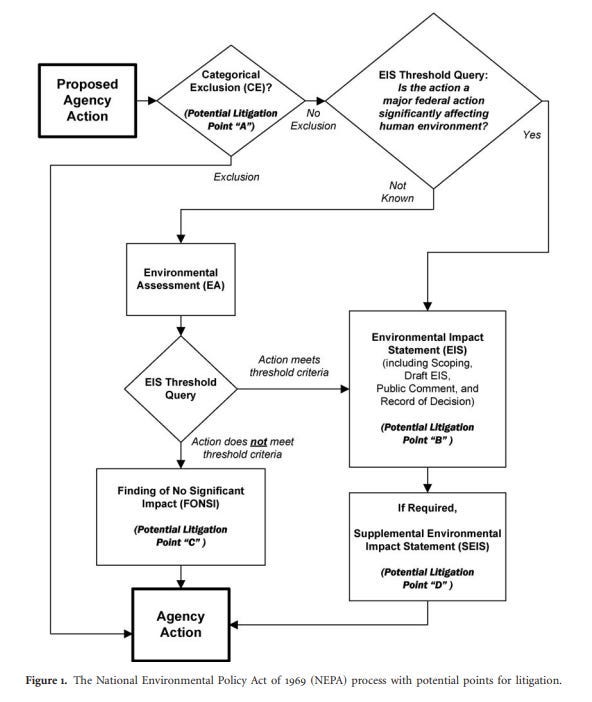

The pyramid below shows how these detailed statements are divided into three tiers. Each U.S. agency has its own NEPA procedures and staff responsible for determining which category a proposed action falls into. As a result of this decentralized system, there’s considerable variability in how NEPA is applied across agencies.

The bottom tier consists of Categorical Exclusions (CEs), which cover most federal agency actions. These require minimal effort but must fall within a predefined and approved category of actions. If an action doesn’t qualify for exclusion, an Environmental Assessment (EA) is conducted to determine whether it will have “significant” environmental effects. If the EA finds significant impacts, an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is required. The EIS provides a detailed analysis of the action’s effects and explores alternative approaches.

The process flow for the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 is shown below. If a proposed action doesn’t meet the threshold for a full EIS, agencies can instead issue a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI)—a way to sidestep the EIS requirement while still demonstrating due diligence. For example, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) required SpaceX to implement 75 mitigation measures for its Boca Chica launch site, including preparing a report on historic events from the Mexican War and issuing notices about lightning during sea turtle nesting season.

The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), created by NEPA, is an executive branch organization responsible for overseeing the law’s implementation. In 1977, President Carter issued an executive order granting the CEQ authority to issue binding NEPA regulations. The following year, the council’s guidelines established the modern NEPA process still in use today.

NEPA’s Two Killers: Time and Uncertainty Costs

As Brian briefly notes in his post, it’s important to understand that NEPA is primarily a procedural requirement—it doesn’t mandate specific mitigation measures or prevent adverse environmental impacts. Its purpose is to ensure that agencies thoroughly assess and document those impacts before taking action. Unfortunately, the biggest bottlenecks to clean infrastructure projects aren’t technical challenges, but rather the (i) time and (ii) uncertainty costs introduced by the NEPA process.

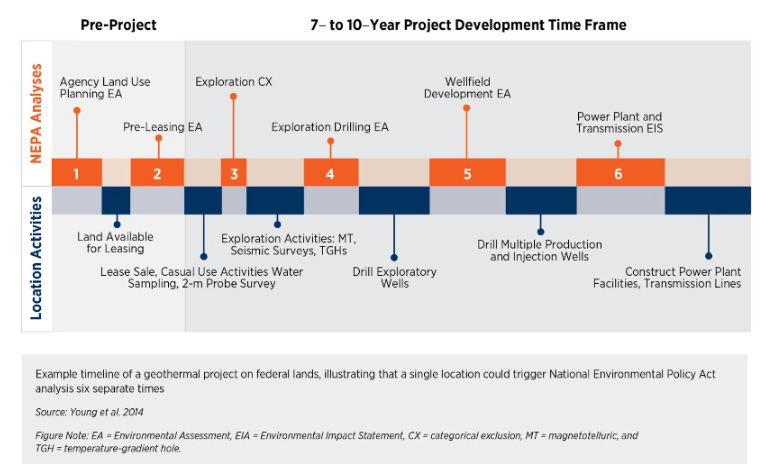

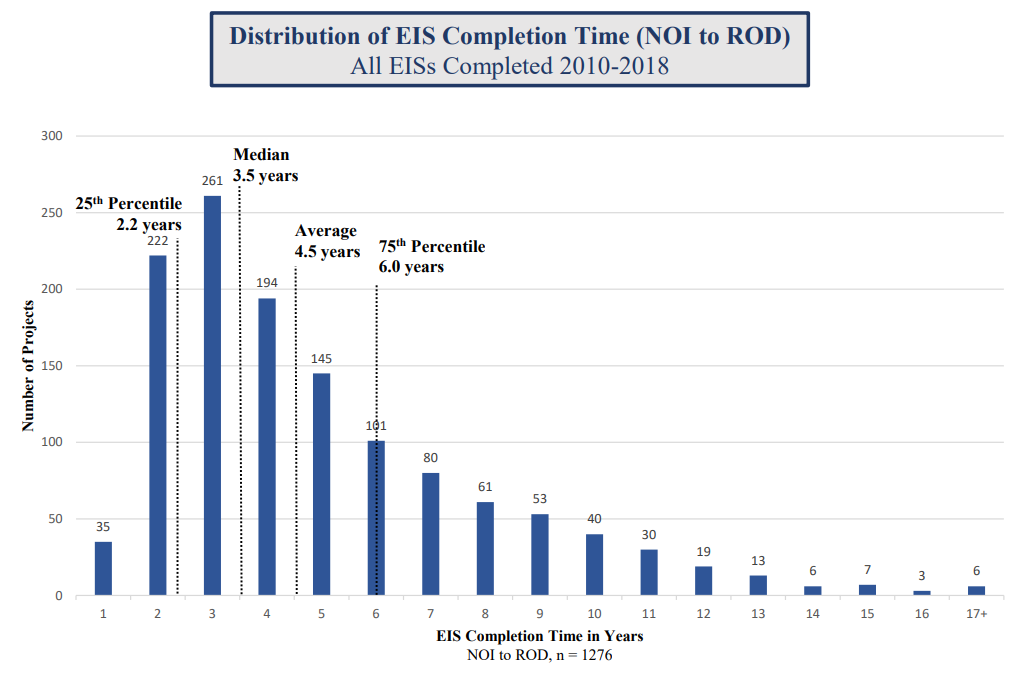

Let’s start with the time costs—by far the most significant bottleneck. The problem with Environmental Impact Statements (EISs) is that they take years to prepare and must be reviewed and approved before a project can even begin. On average, an EIS takes a staggering 4.5 years to complete—and that number is rising. That’s 4.5 years before construction even starts! According to the 2018 Annual NEPA Report, EIS preparation times increased by nearly 50% between 2000 and 2018. For some agencies, like the Federal Highway Administration, the average climbs to 8.6 years. These delays don’t just slow down projects—they can also cause environmental harm. For example, the NEPA process delayed prescribed burns intended to prevent the 1999 Six Rivers National Forest Wildfire, ultimately contributing to the destruction of natural habitats.

Uncertainty costs can be just as damaging. NEPA is the most litigated environmental law in the U.S., with courts responsible for enforcing compliance. Roughly one in every 450 federal actions under NEPA is challenged in court, and more than one in ten cases results in a temporary or permanent injunction. These injunctions are often used strategically by activists to halt projects they oppose. For developers looking to build new infrastructure—whether it’s a geothermal plant, an energy storage facility, or a transmission line—this creates a paralyzing environment. They can’t even estimate basic project parameters like timelines or permitting costs. And because the mere threat of litigation looms large, agencies often overcompensate by creating “litigation-proof” NEPA documents, further dragging out the process—regardless of a project’s actual environmental impact.

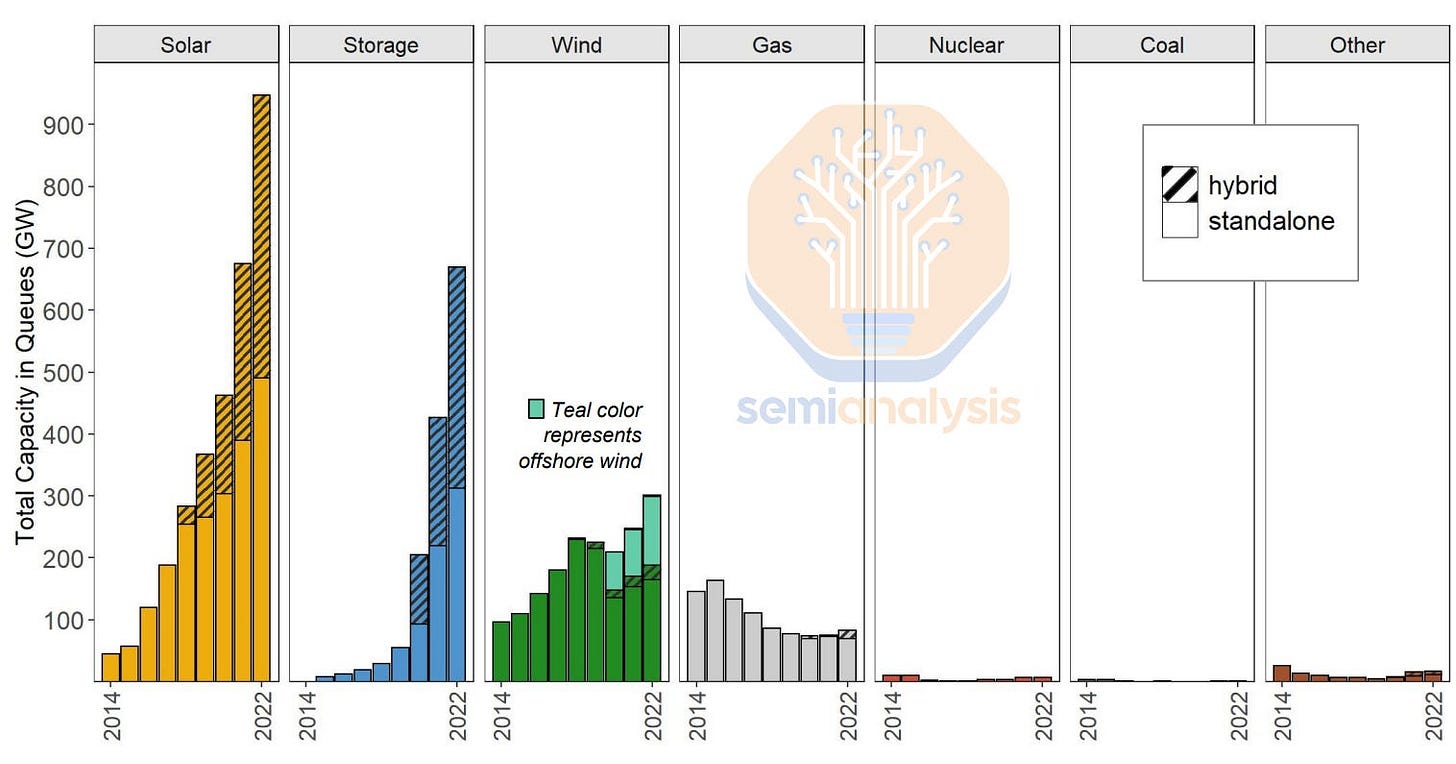

There’s no way to sugarcoat it: the clean energy transition is being strangled by green tape. The U.S. cannot meet its decarbonization goals—or scale its energy capacity fast enough to compete with China (see the geopolitics section of the previous post)—without reducing regulatory barriers. It’s deeply frustrating that the very regulations designed to keep America “green” are now blocking the construction of nearly 2,000 GW of clean energy capacity.

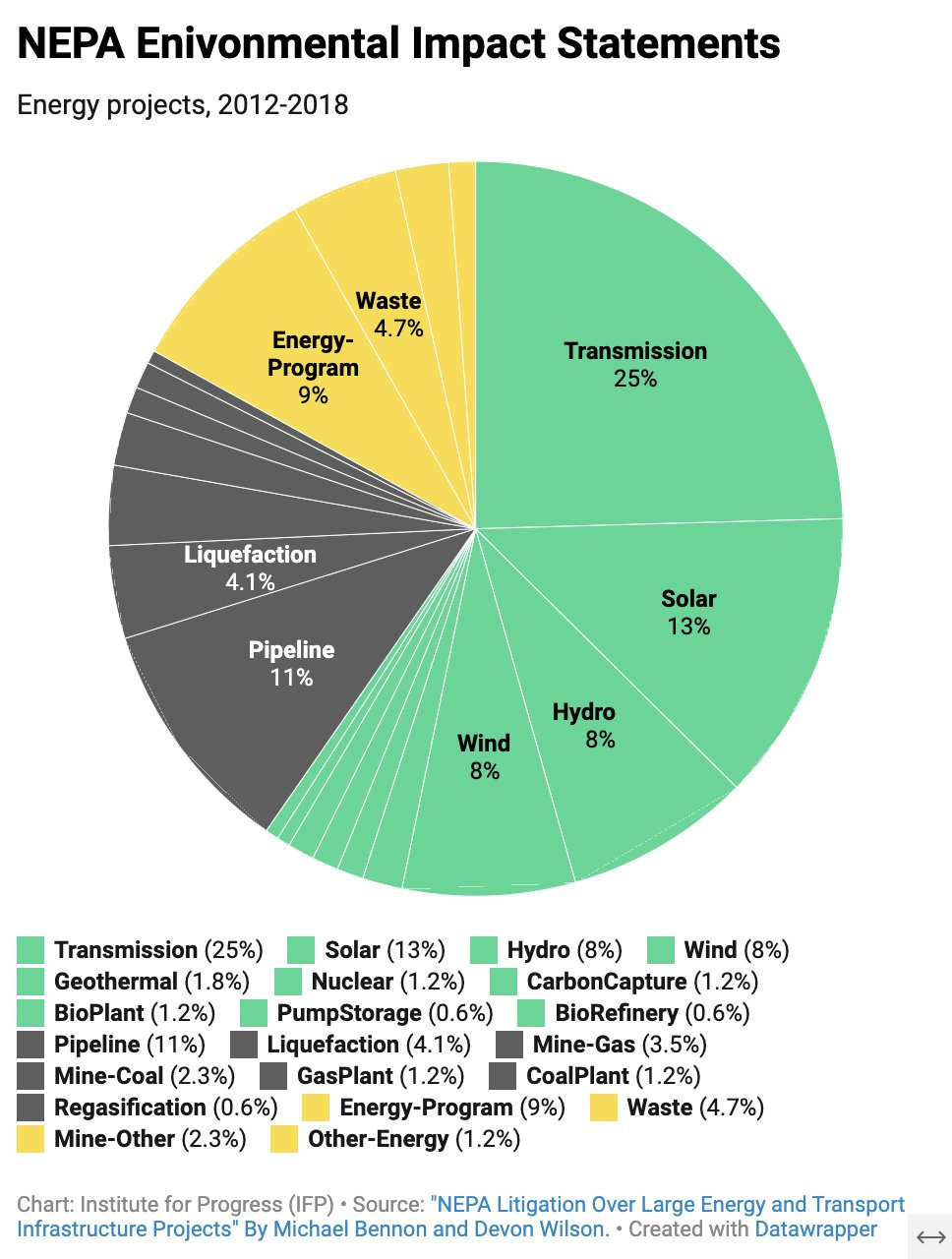

The prolonged NEPA process ultimately reinforces the status quo. The charts above make this clear: only about a quarter of EISs are tied to gas pipeline or coal plant projects, while more than half involve clean energy—especially when transmission lines are included. The imbalance is even more striking when comparing total U.S. installed capacity to the active interconnection queues in 2023. The queued capacity is nearly twice what’s already installed, and about 90% of those queued projects are clean energy. In contrast, gas projects make up only a small fraction. I’ll revisit this point in the next section.

Why I’m Cautiously Optimistic about Trump’s January 2025 Executive Orders on Energy

The closest the U.S. has come to NEPA reform was in 2022, when Senator Joe Manchin proposed a series of changes aimed at easing regulatory barriers to infrastructure development. His proposal included a two-year time limit for NEPA reviews on major projects and a one-year cap for minor ones. He also sought to shorten the window for legal challenges to agency permitting decisions—from six years to just five months.

What ended up happening to Manchin’s proposals? They ultimately failed. An ardent group of climate progressives opposed the bill, mainly because the proposed changes were seen as a vehicle to fast-track the Mountain Valley Pipeline—a 304-mile natural gas project that Manchin strongly supported. Despite the broader relevance of the reforms, their association with the pipeline turned the proposal into a political flashpoint, and the bill was blocked.

As Eric Levitz argued in his piece, ‘Climate Hawks Should Have Given Joe Manchin His Pipeline,’ by blocking Manchin’s proposals, progressives revealed that they prioritized halting fossil fuel development over accelerating the clean energy build-out. In doing so, they made a serious strategic blunder. A prolonged NEPA process disproportionately harms clean infrastructure projects compared to existing fossil fuel infrastructure, ultimately slowing the transition they’re trying to achieve.

Unlike Joe Manchin, President Trump is likely to face little resistance from Congress before the midterms. Backed by a strong political mandate, he signed three energy-related executive orders (EOs) on January 20th. The three EOs are:

The second and third executive orders on the list are disappointing—though not unexpected, given the president’s track record.

In the second executive order, Trump makes it clear that his administration views energy policy through the lens of climate politics and culture wars, rather than as a matter of increasing supply. The order narrowly defines “energy” or “energy resource” as crude oil, natural gas, lease condensates, natural gas liquids, refined petroleum products, uranium, coal, biofuels, geothermal heat, the kinetic movement of flowing water, and critical minerals—explicitly excluding solar, wind, storage, and other clean energy infrastructure.

The third executive order effectively brings offshore wind projects on federal lands to a halt. It suspends the approval of leases, permits, and loans for both offshore and onshore wind energy developments.

While the second and third executive orders are deeply disappointing, Trump’s ‘Unleashing American Energy’ EO may ultimately outweigh the damage caused by the others. Why? Because, as we've emphasized throughout this post, the final bottleneck to accelerating clean energy development isn’t technological or economic—it’s regulatory. Clean energy already leads in cost-effectiveness, as demonstrated by levelized cost of energy (LCOE) metrics. This executive order has the potential to unlock the massive backlog of solar, storage, and wind projects currently stuck in permitting queues—representing at least three times the capacity of gas pipelines awaiting approval (see the chart above from Semianalysis).

Section 5 of ‘Unleashing American Energy’ begins by revoking Carter’s 1977 executive order that gave the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) the authority to enforce NEPA regulations. In its place, the CEQ is directed to “expedite and simplify the permitting process within 30 days.” The order also mandates the creation of a working group to ensure that “all agencies must prioritize efficiency and certainty over any other objectives, including those of activist groups.” While the EO is still new, it will likely lead to three significant changes: narrowing the definition of what qualifies as a “major federal action” (see the first paragraph of this post for context), establishing bright-line thresholds for environmental significance, and dramatically shortening the public comment period.

I’ll write a follow-up post once CEQ provides updated and clear guidance based on Trump’s EO. In the meantime, we are finally one giant step closer to genuinely unshackling and unleashing American Energy!